Find My Friends in a Pandemic: The Future of Contact Tracing in America

Anna McCaffrey and Samantha Stroman. "Find My Friends in a Pandemic: The Future of Contact Tracing in America." CSIS Commission on Strengthening America's Health Security, Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 16, 2020. Accessed October 01, 2025. https://healthsecurity.csis.org/articles/find-my-friends-in-a-pandemic-the-future-of-contact-tracing-in-america/

Today, the United States faces unprecedented twin crises. The Covid-19 pandemic is racing across the globe, having infected over 2 million people and killed over 130,000 at time of publication. Until we have a vaccine, social distancing measures are the most effective tools at governments’ disposal to stop the spread of the virus and prevent even higher death rates. While social distancing measures can “flatten the curve,” they have also frozen the global economy, generating the greatest economic shock in modern history.

Bringing an end to the public health and economic crises in the United States will require a widespread expansion of testing, contact tracing, and isolation. This is the only path out of the nation-wide social distancing guidelines that are saving lives but suffocating the economy. But contact tracing—identifying everyone who has interacted with a confirmed Covid-19 case—is a resource- and time-intensive effort, and to keep up with the rapid and pervasive spread of Covid-19 will likely require some degree of digital monitoring using cell phones.

Indeed, when we consider other countries that have succeeded in curbing their epidemics, digital technologies emerge as a key pillar of their Covid-19 responses. In Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea—countries that have been lauded for implementing rapid and highly aggressive public health responses that kept case counts low while keeping their societies relatively open—technology plays a central role in case finding and contact tracing efforts. China took the most extreme approach, repurposing its extensive surveillance apparatus to track and slow the spread of Covid-19.

In each of these countries, the government is using digital technologies to monitor transmission and track and enforce compliance with social distancing requirements. However, the use of digital surveillance technologies in these countries involves an invasion of privacy that most Americans would resist. As U.S. officials begin to devise strategies for opening up society without reigniting outbreaks, is there anything that they can learn from these other countries? Or are the approaches taken in Asia simply not replicable in the United States?

South Korea

The government of South Korea, praised for its strong testing, contact tracing, isolation, and quarantine measures, has succeeded in containing the spread of Covid-19. Technology has been central to the government’s containment strategy.

The government of South Korea sends emergency phone alerts detailing new confirmed cases and their movements to people in close proximity to the new cases, intending to warn people of possible contact and exposure. Those who believe they may have had contact with confirmed cases are encouraged to seek testing. These emergency alerts have stirred controversy over the level of personal detail shared and the potential for public disclosure that would violate personal privacy. In several instances, the identity of confirmed cases has become known publicly, generating considerable stigma and speculation on the private lives of those individuals.

The alerts have also driven customers away from some of the businesses visited by confirmed cases. This trend has in turn made businesses targets for fraud, with people calling businesses claiming to be confirmed cases and seeking bribes in return for not informing authorities that they had been to those businesses.

Coupled with these phone alerts, the government of South Korea is publishing the movements of confirmed Covid-19 cases on a central website, with the goal of informing residents of potential exposures. The government is using information, including cell phone data, credit card records, and interviews with confirmed Covid-19 patients, to inform its online map.

In response to the increasing use of digital surveillance for Covid-19 tracking, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) of Korea has said that the location details being released are “unnecessarily specific,” fueling psychological distress and stigma and disincentivizing self-reporting of symptoms. In particular, the NHRC took issue not with the collection of personal information but with its release to the public and recommended aggregating some information and redacting certain personal details.

Despite human rights concerns, recent public opinion of the South Korean government’s response to Covid-19 has been generally positive. South Korea’s Covid-19 response—which involved not only digital surveillance but also a massive testing effort, rapid dissemination of personal protective equipment, and close coordination across the government and the private sector—has been extremely successful, keeping the country’s reported cases at about 10,000 and its reported deaths below 250.

Singapore

Today, Singapore is facing a dramatic surge in new cases linked to the return of Singaporeans from overseas after many countries urged citizens to return to their home countries in mid-March. In the early stages of its outbreak, Singapore had managed to avoid a lockdown and widespread restrictions on movement. But following the recent spike in imported cases, the government has closed schools and non-essential businesses and is recommending that people stay home as much as possible.

Despite this recent setback, the government’s initial response to Covid-19 was highly effective and widely praised. Singapore learned the lessons of SARS well and launched a coordinated, effective response in the early days of the outbreak. Facing significant risk of spread given its proximity to and high interconnectedness with China, the government of Singapore had to act quickly or face catastrophe. Its swift, aggressive actions made its response a model for the rest of the world.

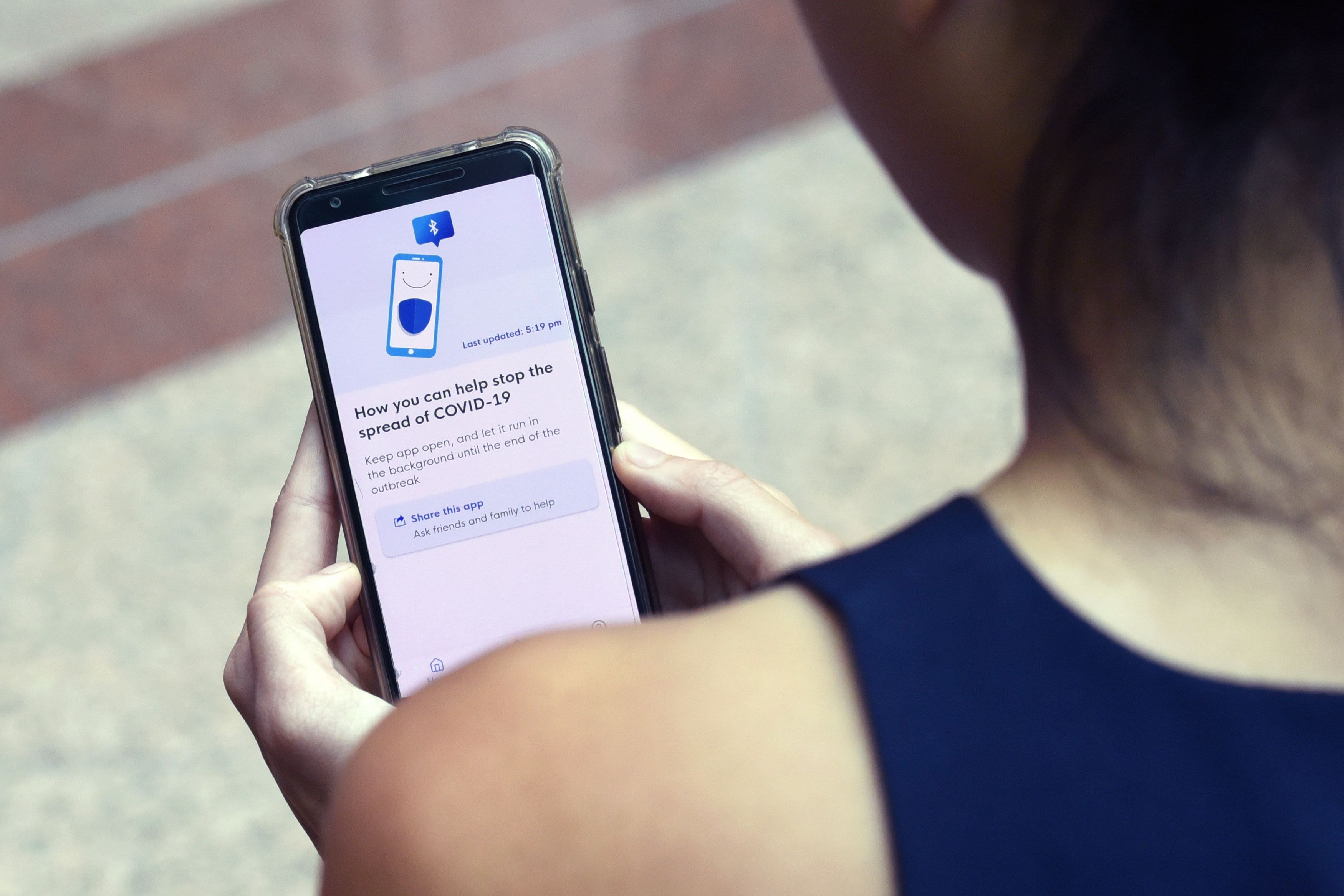

A key element to Singapore’s success in containing the outbreak has been the government’s use of surveillance technology to monitor individuals’ behavior and enforce public health directives. The government created an app, TraceTogether, that alerts users if they may have been in close contact with a confirmed case. Phones with the app exchange Bluetooth signals when users come into close contact, and information on these contacts feeds into a government database tracking possible Covid-19 cases and exposures.

TraceTogether data is encrypted and anonymized, and sharing data with the government is optional. Use of the app is technically voluntary but strongly encouraged by the government and entities such as schools and private companies. While government surveys show a majority of Singaporeans approve of how the government handles personal data, its surveillance and collection of data as part of the Covid-19 response has stirred concern among both public health experts and civil liberty advocates.

Taiwan

The government of Taiwan has also prioritized technological innovations in its response to Covid-19. At the start of the outbreak, Taiwan established a mobile system to expedite airport screenings to prevent the importation of cases from other countries. The Entry Quarantine System allows travelers with Taiwanese mobile phone numbers to scan a QR code (a unique bar code) upon arrival at Taiwanese airports. The QR code leads to an online health declaration form. Upon completion of the form, low-risk travelers are sent a health declaration pass by SMS to their phones, which expedites movement through immigration clearance. The Taiwan Centers for Disease Control describes the system as “4 simple steps: scan the QR Code, fill out the form, get health declaration pass via SMS, and show the pass on your mobile phone.”

More recently, as Taiwan has experienced a rise in imported cases, the government has imposed a strict 14-day quarantine for all arriving travelers, and the government is using more controversial technological tools to enforce these quarantine orders. Taiwanese authorities have used mobile phone location tracking services to build “electronic fences” around individuals in home quarantine. The system uses regular phone signals to determine individuals’ locations rather than relying on an app or other additional system. Government officials are alerted if quarantined individuals leave their homes or turn off their phones, indicating a possible breach of quarantine. Government officials call quarantined individuals twice daily to check for the onset of symptoms and to ensure that phones are not turned off.

When individuals who are under quarantine orders trigger the alert system by moving too far from home or turning off their phones, police are dispatched to confirm their locations. In the case of one American University student who was quarantined after returning home to Taiwan, police were dispatched when his phone simply ran out of batteries and powered off. High fines are imposed on quarantine violators.

While some have expressed concerns about the severity of this approach, public opinion has been generally supportive of the government’s Covid-19 response, including the use of digital surveillance. The government claims that they will end the current tracking system when the pandemic ends.

China

Throughout January and February 2020, the world looked on as China imposed a series of draconian measures to contain the novel coronavirus. China deployed the full power of its surveillance state to both communicate and strictly enforce its social distancing, testing, contact tracing, and quarantine measures.

The Chinese government worked closely with tech companies such as Tencent, which owns the widely used messaging app WeChat, to streamline and individualize guidance around travel and quarantines. Users type their unique Chinese identification numbers into WeChat, which compiles data on the user’s health, recent travel history, and contacts. Users are assigned a Health Code based on a traffic light color system that dictates whether they need to self-quarantine or whether it is permissible to travel. Chinese officials have not been transparent about what exactly triggers changes in the color system. Users also receive alerts about people living or working nearby who are confirmed positive or contacts of confirmed positive cases.

A “green code,” indicating freedom of movement, is both prized and precarious in China. Walking into a grocery store or a bank and crossing paths with someone who subsequently tests positive for Covid-19 can result in a demotion to yellow or red, resulting in isolation or quarantine. In Wuhan, which recently “opened up” following a nearly 3-month-long lockdown, a green code is required for any significant movement, including departure from the city.

The Chinese government has also put to full use its ubiquitous—and controversial—camera surveillance capacity to enforce its public health guidelines. Artificial intelligence technology is used in tandem with facial recognition technology to detect if someone who is supposed to be self-quarantining leaves an apartment. Drones equipped with cameras and loudspeakers are used to determine whether people are wearing masks when they go outside their homes and to transmit stern instructions to those not wearing masks to return home immediately to put them on.

For months, public health experts and civil liberty advocates have expressed alarm at the severity of China’s response, including its invasive surveillance practices. However, the Chinese government does appear to have succeeded in reducing the Covid-19 case load from a peak of 3,500 daily cases in February to zero in mid-March (although experts are increasingly questioning the veracity and completeness of China’s official figures).

The Way Forward for the United States

Contact tracing will be central to the next phase of the Covid-19 response in the United States, and digital technologies will be required to scale this effort across the country. This will likely involve a larger government role in monitoring and surveilling individuals’ health statuses than Americans have ever seen before. But U.S. officials do not need to replicate the invasive approaches used in Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and China in order to end the epidemic.

Contact tracing traditionally involves a public health official calling a person who has tested positive for Covid-19 and discussing the person’s health history and recent interactions. The public health official then tracks down the person’s contacts to discuss their potential exposure, isolation measures, and access to testing. It takes three days, on average, to track down all contacts of one case using manual contact tracing methods. While manual contact tracing is resource- and time-intensive, it will undoubtedly be a cornerstone of expanded contact tracing efforts. Massachusetts is one of a handful of states launching new Covid-19 contact tracing initiatives that will be staffed by hundreds of contact tracers.

But because Covid-19 spreads so rapidly and because the virus is already so pervasive in the United States, a digital effort will be needed to supplement traditional methods and track all possible Covid-19 transmission chains throughout the country. The United States should therefore pursue a hybrid approach, combining manual and digital contact tracing methods that can be scaled across the country, protecting patient privacy while stemming the spread of the disease.

The federal government could help to finance the development of a mobile phone application designed to alert users when they may have come into contact with someone who has tested positive for Covid-19. But instead of using security camera footage, credit card transactions, or compulsory GPS data, an American application could utilize Bluetooth technology, which can show whether people have crossed paths without tracking or publicizing location data. Apple and Google recently announced a joint effort to develop a Bluetooth-based contact tracing tool, to be released in the coming months.

A Bluetooth-based application is an important first step in establishing a digital contact tracing system that protects civil liberties and patient privacy. The Center for American Progress has outlined several additional steps that could be taken to protect privacy as a digital contact tracing system is rolled out nationally, including housing the data with a trusted, nonprofit entity, prohibiting the sharing of data with third parties, and automatically deleting the data after 45 days.

These privacy protection measures notwithstanding, a heightened degree of monitoring at the individual level will be needed to allow people to return to school and work safely. A Bluetooth-based application would need to be used widely—and perhaps even become compulsory—in order for it to be effective. Some experts have recommended that downloading such an application should be a prerequisite for receiving a Covid-19 test. The application could ultimately incorporate an immunity certification system, which at the extreme could require showing proof of immunity before using public transport or returning to work.

This may be a bitter pill to swallow in the United States. Americans are wary of mass data collection after experiencing repeated data breaches and gross violations of digital privacy in recent years. A national, multisectoral effort involving leaders from government, academia, the faith community, and the tech sector will be required to convince Americans of the need for robust contact tracing in order to reopen society incrementally—and safely. Americans will need to believe that these digital tools will guarantee their health and safety, their privacy, and their return to normalcy. Ultimately, tradeoffs will be necessary in order to stop the spread, prevent resurgent outbreaks, protect the vulnerable, and unfreeze the economy.

Anna Carroll is an associate fellow for Global Health Security with the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. Samantha Stroman is a program manager with the Global Health Policy Center at CSIS.

This commentary is a product of the CSIS Commission on Strengthening America’s Health Security, generously supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Commentary is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2020 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.