Fentanyl Opens a Grave New Health Security Threat: Synthetic Opioids

J. Stephen Morrison and Emily Foecke Munden. "Fentanyl Opens a Grave New Health Security Threat: Synthetic Opioids." CSIS Commission on Strengthening America's Health Security, Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 18, 2019. Accessed December 21, 2023. https://healthsecurity.csis.org/articles/fentanyl-opens-a-grave-new-health-security-threat-synthetic-opioids/

China’s commitment to ban fentanyl as a drug class, a welcome announcement at the December 2018 G20 summit in Buenos Aires, was just the most recent, powerful signal of the growing understanding that fentanyl, the front edge of a new era of synthetic opioids, poses a grave, direct health security threat. Fentanyl is extraordinarily lethal and is cheap and simple to produce, minuscule in size, easily transported, and highly addictive. The danger of fentanyl is felt most immediately by Americans and Canadians, but as the Chinese announcement suggests, it is felt by the Chinese and the citizens of other nations as well. In the short space of a few years, fentanyl has swiftly become a forbidding new global threat requiring the diplomatic attention of the world’s most powerful statesmen and women. In North America, fentanyl’s direct causal linkage to startling rises in opioid overdose deaths has stirred urgent U.S. and Canadian policy action, centered on what measures might effectively arrest this threat. There has been much progress at home and abroad despite the complex difficulties in disrupting both fentanyl’s production—principally in China—and its international delivery pathways, the inadequacy of tools to ascertain when fentanyl-laced heroin is lethal, and the very protean nature of synthetic opioids, which has opened the door to the development of successive new molecular analogs that outrace regulatory authorities.

U.S.-China diplomatic cooperation over fentanyl has advanced even as trade, security, and other critical dimensions of the bilateral relationship have become deeply frayed. In this new health security arena, U.S. and Chinese national interests align: each is motivated to take higher-level collaborative action to protect their perceived national sovereign interests. In the face of mounting deaths in the United States, we saw in 2018 accelerated, bipartisan legislative action by Congress, signed into law by President Trump. (We see a parallel mobilization in Canada.)

But it is still early days in understanding and battling this new phase of synthetic opioids and the proliferating health security threats it poses. The curve of ever-higher fentanyl-derived deaths has not yet been bent in the United States and Canada (though recent data shows downturns in some key places). Newly legislated steps to control mail traffic and the importation of fentanyl have not yet been tested. Despite our common interests, it is not clear whether China is truly committed to following through on its promises, and China may be constrained by its own lack of capacity and political will, perhaps compounded by the worsening of U.S.-China relations. Long-term, we do not fully understand the implications of a scientific transformation in illicit drug manufacturing, unlike anything we have faced before, which will continually throw forward dangerous new molecules and test our ability to devise new capacities—in diplomacy, diagnostics, regulatory regimes, industrial norms, supply chains, and communications—that will allow us to get ahead of this revolution.

Fentanyl: A Grave External Threat

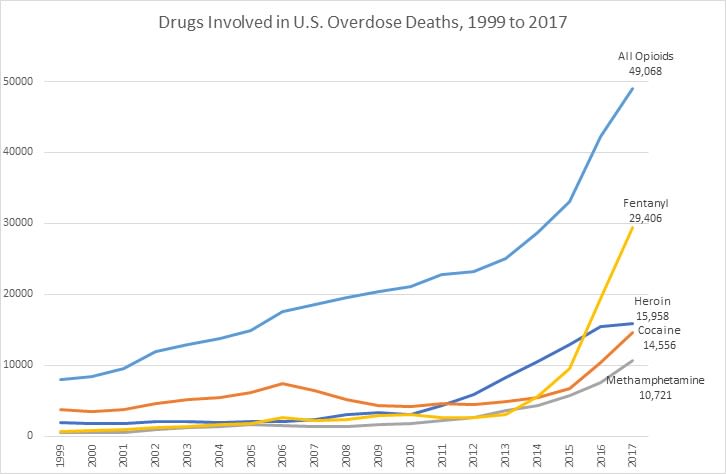

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, is now widely understood to be an exceptionally lethal new threat to the health security of Americans. Average life expectancy in the United States declined in 2016 and 2017 for the first time in decades, partly due to the rise in opioid overdose deaths, which totaled 72,000 in 2017—a new record. Almost 30,000 of these deaths in 2017 were directly attributable to fentanyl, the drug category with the steepest increase in lethal overdoses over the last several years.

While fentanyl is legal with a prescription, it is commonly trafficked and consumed illicitly. Drug cartels now commonly cut heroin with fentanyl to increase both potency and profitability. The cartels increasingly rely on fentanyl cheaply sourced from China but can produce their own fentanyl as needed. Most heroin enters the United States via Mexican drug cartels, which means, in practice, a large proportion of fentanyl enters the U.S. black market through Mexican smuggling channels, such as the Tijuana/San Diego corridor controlled by the Sinaloa Cartel.

All synthetic opioids except for methadone are more powerful and deadly—in minuscule, easily concealable doses—than plant-based opioids. Users often have no visibility into the strength of the dose they are consuming, which places them in acute danger of overdose and death. For those without an acquired tolerance, the lethal dose of fentanyl is two milligrams, about the size of two grains of salt. Those who overdose on fentanyl often do not respond to standard doses of naloxone, the overdose reversal drug. Exposure to fentanyl poses dangers to anyone proximate to users—health care providers, law enforcement, and family members or any other person who may have accidental contact.

The Front Edge of a Historic Moment

We are at the front edge of a scientific transformation in the way opioids are produced. We have entered a world of synthetic opioids that is capable of rapidly generating further analogs.

Synthetic man-made drugs do not rely on agricultural cultivation, ample land, harvest, processing, and bulk transport infrastructure (as required, for instance, for poppies). They now dominate illicit opioids in the United States. These synthetic opioids, with fentanyl the principal synthetic opioid threat, are produced easily and cheaply in labs from readily available precursor chemicals. Most fentanyl originates in China, where an estimated 160,000 chemical and pharmaceutical manufacturers operate legally, illegally, and frequently in a grey zone that straddles the two. Beijing’s regulatory control over what happens in China’s far-flung provinces is often remarkably weak and complicated by corruption. There are also reports of early fentanyl production or trafficking in India, Pakistan, Thailand, Mexico, and Canada. On the home front, illicit labs in garages and basements across America produce hundreds of thousands of counterfeit pain pills laced with fentanyl obtained from China.

Fentanyl analogs allow manufacturers to stay a few steps ahead of the law. By simply adding or removing an atom, it is possible to create new molecules that have the same effects as fentanyl but are not legally classified as such. These new derivatives can be manufactured just as quickly as fentanyl itself and are equally deadly in tiny amounts. Analogs can evade lab testing by hospitals and law enforcement, as there are delays introduced by including novel synthetic opioids in routine testing.

Evidence shows that illicit manufacturers are already moving beyond fentanyl-based analogs to other synthetic opioids like U-47700 and MT-45. And the numbers of novel synthetic opioids seized in the United States are rapidly rising. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) 2017 Emerging Threats Report, 55 percent of the synthetic opioids identified in 2017 were identified for the first time that year.

Unified U.S. Action Elevates Fentanyl

The Trump administration and Congress have recognized fentanyl as a grave threat to the U.S. public. In October 2018, President Trump signed into law the Support for Patients and Communities Act, a sweeping package of bills aimed at fighting the U.S. opioid crisis, which passed Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support. The package calls for improved U.S. interagency coordination on improving fentanyl detection and testing at U.S. border checks and includes the Synthetics Trafficking and Overdose Prevention (STOP) Act of 2018, legislation that strengthens standards for international packages at the U.S. Postal Service (the primary supply route for fentanyl into the United States).

In February, the DEA issued a two-year temporary order that proactively regulates all fentanyl analogs as a single class, a key change from its previous orders that regulated each new fentanyl analog individually. U.S. law enforcement has also turned up the public pressure on China in the past year: eight Chinese nationals have been indicted for fentanyl trafficking under U.S. federal law with assistance from the Chinese Ministry of Public Security—although none have been extradited to the United States because the United States and China do not have an extradition treaty—and five have been designated for U.S. sanctions.

China has also taken substantial unilateral actions, including labeling 25 fentanyl analogs and 2 precursors as controlled substances and announcing reforms to its chemical industry regulations and major chemical industry regulatory bodies.

U.S.-China Alignment

The single most significant action from China on fentanyl is the commitment President Xi made to President Trump at a dinner on the sidelines of the November 2018 G20 summit, which was followed by a statement reiterating the commitment from the Chinese foreign ministry. By agreeing to label fentanyl as a class of controlled substances, China aligned itself with U.S. policy. The systematic criminalization of the trade of fentanyl and all current and future fentanyl analogs—by both the United States and China—is a diplomatic milestone.

Even though the U.S.-China relationship is in the midst of a fraught period of escalating confrontations, it has been possible to strike this agreement on the threat of fentanyl—based on mutually shared interests. The United States needs a shared regulatory framework with China if it is to stem the rise of U.S. fentanyl deaths. China, for its part, fears the rise of fentanyl-derived deaths among its population, while also fearing reputational damage, especially to its global pharmaceutical companies.

The focus now shifts to China’s follow-through: it will need to amend its current laws before the ban can take effect and outline how exactly it will enforce new regulations.

Pathways for U.S. Action Today and in Future Battles against Synthetic Opioids

Despite the breakthroughs of 2018, the United States (and others) are still struggling to catch up and get ahead of this dynamic and dangerous new era of synthetic opioids. Part of that is the widening realization that the health security threat we face encompasses far more than just fentanyl per se and far more than just the U.S.-China relationship.

We can see more clearly today the several critical pathways for U.S. action to combat fentanyl and the uncertain future of synthetic opioids. Each path is essential, and each is complex and rich in challenges.

There is the need for tighter regulatory harmonization internationally, continued sanctions and prosecution, expanded technical expertise, more extensive sharing of data and best practices, improved diagnostics, improved tracking and reporting of new analogs, and strengthened track-and-trace of items in the last mile of transport to an airport or seaport in exporting countries. The UN drug control structure, established in the early 1960s, struggles to keep up with the synthetic opioids threat and is in visible need of reform. Much more needs to be done to engage private corporate sector actors over norms and practices to enhance self-regulation and timely reporting and to control access to fentanyl precursors.

All of these pathways rely on continued U.S. leadership, guided by sustained U.S. high-level diplomacy, rooted in the belief that multilateral solutions remain essential. The nucleus of key partners will include China, Mexico (for which there has been parallel diplomatic progress, much like with China), Canada, the United Kingdom, and the EU member states. A U.S.-China-Mexico-Canada dialogue hosted by the United States to cooperatively address fentanyl and heroin would be a significant step forward and is a feasible goal in 2019 that could build on recent diplomatic momentum. Africa will also be an important player, as the Chinese pharmaceutical industry is seeking to build capacity and advance access on the African continent. Progress is achievable in the G7, the G20, the annual World Health Assembly, and the UN’s Commission on Narcotic Drugs.

Synthetic opioids now occupy a highly visible place among emerging new priorities of health security. They are a real threat that require real and durable solutions that stretch well beyond our borders and test our political will, diplomatic savvy, and a range of institutional capacities. Much progress has been made just recently, but it is still early days.